How Stress Shapes the Mind and Body: A Look into Developmental Psychobiology

CTD Director, Susan Corwith, spoke with Emma Adam, Edwina S. Tarry Professor of Human Development and Social Policy at Northwestern’s School of Education and Social Policy, and Faculty Fellow at the Institute for Policy Research about her work as a developmental psychologist and what she has learned about stress, biology, and the wellbeing of children and adolescents.

Developmental Psychobiology and What It Can Tell Us

Emma Adam is an expert in the developmental psychobiology of stress and sleep, and while the description may sound complicated, the work is centered on understanding stress and how it affects the development of our bodies and our brains. Stress is more than a feeling. It is also a set of biological reactions in the body and those biological reactions have implications for cognition, health, and other outcomes.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · Stress and the Study of its Effects on the Body

What is unique about Adam’s lab is her focus on collecting data in real-time during day-to-day activities—what can be termed “naturally occurring stress”—in the lives of adolescents. Her earlier work established that it is possible to “see” stress in cortisol samples (collected in saliva) as stressful situations are occurring, and her more recent work has been answering questions like what are the things that are stressing kids out in ways that matter to their biology and what are strategies for mitigating the impacts of stress on the body. Understanding how stress affects young people’s bodies and development could have significant implications for how young people are taught to recognize and respond to stressors and how parents and educators interact with young people and create supportive living and learning environments.

The Research on Adolescent Stress Biology

Adam has conducted novel research, combining behavioral and biological data to explore how different types of experiences and activities impact biology, specifically looking at cortisol levels. The ubiquity of cell phones and technology have made data collection much easier and less invasive than in the past. The young people who participated in Adam’s research received periodic push notifications via their cell phones that signaled them to submit a diary entry—sharing where they were, what they were doing, and what they were thinking and feeling—and to collect a saliva sample so that the cortisol level could be compared to the timeline of the activity on which they were reporting. This research provided a variety of insights about the sources of stress and the effects of those stressors on the body.

Insights about Stress for Adults Working with Young People

Drawing from her stress biology research, Adam says, “the most frequent thing that [adolescents] report is school related stress.… but the second most frequent is social stress, and it turns out—and this is interesting for what you do at CTD—that it’s actually the social stress that has the biggest impact on the biology, and not the academic stress.” The academic stress becomes problematic or becomes stressful when there are social dynamics behind it. There are many sources of stress, yet not all stress is negative nor does all stress have a significant impact on a young person’s biology and cognitive development. This is an important finding for parents and other adults working with young people.

When individuals experience challenges or are in situations that require thinking, problem solving, or novel social experiences, our human bodies are equipped to respond. These types of experiences usually result in low to moderate levels of cortisol, which sharpens cognition. It is when cortisol levels get too high that it starts to affect another set of receptors in the brain. Adam says in that case, “it actually then focuses your cognition only on the stressor. And it means you can't focus on anything else that you would want to focus on or need to focus on.” It is when the academic stress becomes about the self—self-worth, inclusion, and belonging—that it can often become more problematic.

Social Stressors Are Experienced Differently: The Role of Identity

Inclusion and belonging are complex and go beyond basic social interactions in a school setting. Belonging is tied to our identities, which include race, ethnicity, gender, socio-economic status and more. In Adam’s research, feelings of being alone, feelings of loneliness, or social exclusion were powerfully related to both cortisol levels and sleep patterns. As she explored various aspects of identity—race and ethnicity in particular—and various stressors and impacts, she found students of color had more dysregulated stress hormones and more dysregulated sleep. As a group, they slept less by about half an hour, and in terms of the impact of sleep on health and cognition, half an hour is a significant difference.

Adam and fellow researchers conducted several additional studies, which found that feelings of exposure to discrimination, particularly during adolescence, were associated with dysregulated stress biology both in adolescents and in adults. Not surprisingly, adolescents of color were exposed to much higher discrimination, and that discrimination had larger impacts on their stress biology. These findings led Adam and her team to examine the data further to try to find ways to protect young people, particularly young people of color, from the negative effects of stress on their health and well-being.

Mitigating the Negative Impacts of Stress

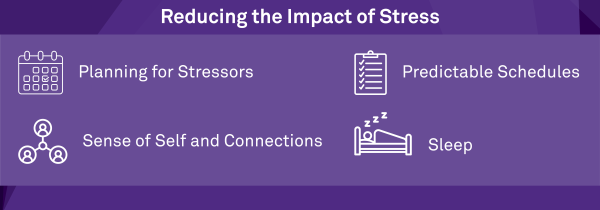

The research is providing insights into what reduces the negative impacts of stress. Below are four factors that stood out.

Sense of Self and Connections: Having a positive sense of self and a network of support proved to be important across all groups of study participants. To address the disparate impacts of stress on students of color, the literature on psychological well-being suggests that having a strong ethnic identity can provide a buffer, particularly to the effects of discrimination. Adam’s research looking at identity as a variable found that even when experiences of discrimination predicted a poor outcome, a strong racial or ethnic identity could at least partially reverse the negative effects.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · Sense of Self and Connections

Predictable Schedule: Setting and keeping a reasonably predictable schedule can help to positively regulate stress hormones, enhance their positive effects, and reduce their negative effects on cognition and health. Humans, in general, benefit from regularity. Our bodies have hormonal rhythms and sleep-wake rhythms. While we can handle some deviation from that regularity like if you need to stay up later one night to study for an exam, for example, it is detrimental if these disruptions are ongoing. “This is why we recommend kids don’t have a big bump in sleep on the weekends, but rather keep a regular sleep schedule that is fairly consistent (and sufficient) across weekdays and weekends,” says Adam.

Sleep: Sleep is another key factor in reducing the negative impacts of stress on the body. Sleep has a complex biological purpose that includes “resetting” our bodies and brains and increasing their ability to manage stress each day. Therefore, attending to sleep behaviors and the environments that make it possible to sleep are important for young people. The quality of one’s sleep, especially over time, affects cognition, mood, and the experience of encountering additional stressors.

Planning for Stressors: Learning to plan for stressors and recognize some stressors as part of learning and growth are also ways to mitigate their effects. Adam explains, “one thing that's really cool in the stress biology is that on days when you are anticipating more challenge or there's something coming up like an exam…your body anticipates that challenge and you get a small surge in stress hormones…. You need that moderate boost in the hormones to mobilize your brain and body for cognition and action.” Preparing for situations can help the body be ready for what is to come and regulate the response appropriately. Like what CTD’s research has demonstrated about psychosocial skills, including self-efficacy, a growth mindset, and self-regulation of emotions, Adam has also found these skills are connected to well-being. Young people who view themselves as capable of understanding and managing their emotions, able to make decisions about their environment, and with the capacity to step back from a task and take a break when needed are on their way to more positive long-term outcomes.

Advice for Educators and Parents

One important takeaway Adam identifies for educators and parents is the “fundamental importance of inclusion and belonging.” It is critical not only to a young person’s emotional well-being but to their long-term health and cognition. Adults need to be aware of and proactively address factors that detract from feelings of safety and connection and help young people build skills that protect them against the negative effects of stressors.

Beyond impacting a student’s attention or ability to learn, stressors can “get under the skin” to affect the body and brain, which means parents and educators also need to consider local, state, and national policies that impact young people’s stress levels (and the stress of those around them including parents and teachers). Having a better understanding of the biological impacts of stress over time is another lens that can make policymakers take the ideas of social safety and emotional safety more seriously.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · Understanding of the Biological Impacts of Stress Over Time

The good news is that many aspects of biology are significantly malleable and responsive to interventions. A lifetime is a long pathway and chain of events, including ongoing changes in stress biology from the prenatal period through older age, and there are many opportunities to intervene and improve outcomes along the way.

Learn More: The Youth Mindful Awareness Program | Improving Well-Being for Adolescents

Currently, Adam is part of a team of researchers from Northwestern University, Vanderbilt University, and University of California Los Angeles that is working on a study of interventions designed to help teens, ages 12-17, cope with stress and improve well-being through mindfulness-based practices. The Youth Mindful Awareness Program (YMAP) process begins with a brief survey about current health (e.g. sleep, appetite, fatigue), moods, and worries. Some participants are then given the option to join YMAP’s Intervention Study, where they may be randomly assigned to the study’s mindfulness coaching program. The goal is to learn how to help young people use strategies that increase positive outcomes.

If you are interested in learning more about the current research that Dr. Adam and her colleagues are doing or have a young person who might be interested and eligible to participate, visit the Youth Mindful Awareness Program (YMAP) website. YMAP is a multi-site research project led by researchers at Northwestern University, Vanderbilt University, and University of California Los Angeles. YMAP is actively recruiting 12–17-year-olds in Illinois, California to participate in the study.

Read More: Research on Reducing Stress Disparities

As noted in the previous article, Adam’s work has revealed racial and socioeconomic disparities in stress, cortisol and sleep. She and fellow researchers are looking at the possible implications for disparities in long-term health and understanding impacts of stress, stress biology, and development for youth of color. If you are interested in this topic, you can find her 2020 chapter on Reducing Stress Disparities with fellow authors Sarah Collier Villaume and Emily Hittner on the Northwestern website.

Revisiting Social-Emotional Learning and Talent Development

In the conversation with Emma Adam, she highlighted the importance of having a community, a strong sense of self and identity, and the need for young people to be able to respond with strategies to experiences that may be stressful. When we look at these ideas from a talent development perspective, they align with what we know about the importance of social-emotional learning and, more broadly, the development of psychosocial skills.

The skills and behaviors involved in promoting talent development help students regulate their emotions, manage their time and planning, develop a healthy self-concept and more. With this in mind, we invite you to revisit our blog from January 2024 where CTD program coordinators Ruth Doan and Nick Kapling discuss how CTD programming supports the development of critical psychosocial skills and why these skills are so important.

Read the Blog Social-Emotional Learning: Inseparable from Academic Rigor