Teaching for Civic Engagement | A Conversation with Matt Easterday

Matt Easterday is an associate professor at Northwestern University in the School of Education and Social Policy. Additionally, he is a Faculty Fellow for Northwestern’s Center for Civic Engagement and a Northwestern Searle Center for Teaching Excellence Fellow. Easterday is actively engaged in the Evanston, Illinois community and with Citizen University, which is a non-profit organization with a mission to build a culture of powerful, responsible citizenship across the country.

Easterday spoke with CTD director, Susan Corwith, about his research, civic engagement work, and the importance of civic education for young people.

Corwith: I am excited to talk with you about the topic of civic engagement, because it relates directly to CTD’s Civic Education Project programs for middle and high school students. In well-designed civic education programs, students are challenged to learn in new ways while building their intellectual capacity and leadership skills for the future. Given the work you do, how would you summarize the goal or desired outcome of teaching for civic engagement, and what are the benefits of early, ongoing exposure to civic education?

Easterday: The desired outcome is developing powerful, responsible citizens. By citizens we mean people who work to improve their communities. It's not about their documentation status, where they were born or anything like that. Civic education provides a great benefit for society by teaching people how to govern themselves and act in the common good.

Unfortunately, we often don’t teach the skills you need to engage effectively in civic activities until young adulthood and sometimes not even then. And there is research by Schlozman, Brady and Verba that the people most able, and most asked, to participate tend to be older, more educated, and have higher incomes, because they have the resources to participate.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · Importance of Civic Engagement

We don’t teach the necessary critical skills, mindsets, and habits for civics young people, if we can’t do civic education early and right, we’re missing out on lifetime of civic engagement – it shouldn’t be something that only happens in retirement for those lucky enough to retire. Early civic education is a benefit to society.

If you feel empowered as a young person to change your community, not only does that make your community better, but you don’t feel that you are at the mercy of the political system. I think that piece is important right now. I believe part of the reason people take elections so hard is because they don't feel like they have any power over it. Knowing how to navigate the system doesn’t just happen. We need to teach people how to be competent citizens.

Corwith: You teach courses to Northwestern students in the civic engagement certificate program. What types of experiences do students have in these courses?

Easterday: There is a one-year sequence followed by two quarters of leadership coaching. In the first-year, students design the campus participatory budgeting (PB) process. They run town halls, which teaches them how to plan events and do outreach. Then, they form a steering committee to plan the PB process, which involves writing a kind of “constitution” or rulebook for how it will be conducted. They also start some policy development work. The focus is on implementation, unlike a policy analysis class where students research and write about national policies that they won’t implement. Instead, they work through details so that if a project were funded, it could be realistically executed. This approach is similar to the skills needed to develop a community development project plan, and they’re doing outreach the entire time.

In the winter, the PB process starts in earnest. Students run idea collection events—community brainstorming sessions. They also develop and facilitate policy development meetings where anyone can contribute ideas for proposals. At the end of the quarter, they hold a vote where the community (in this case, Northwestern) selects the proposals to be funded. This part of the sequence teaches students how to run a democratic process, deliberate, and write policy.

In the spring, they do two sets of events. First, they implement the funded projects, which involves carrying out the plans and is a valuable hands-on community development experience. Second, they hold “Civic Saturday” events—civic-themed gatherings akin to a “civics church” where people discuss topics to build motivation and understanding of what it means to be a responsible, empowered citizen.

After the first year, students in the certificate program receive one-on-one leadership coaching and begin teaching newer students these skills, so they are learning more advanced organizing skills.

In addition, the civics courses are tied to a student-run club, which serves as the ongoing hub for these activities. The club is designed to carry on beyond a ten-week class, which gives students practice running a sustainable organization. This setup also allows students who aren’t enrolled in the class, or those who can’t be, to participate, and it contributes to the real-life skill building and networking students need for the long term.

Corwith: What do you think is important to keep in mind when teaching civics at any age or developmental level? Where are some of the challenges for educators, curriculum developers, and school leaders?

Easterday: A challenge with teaching civics is that to do it well, you can’t just teach it in a classroom or through a few hours of volunteering; students need to be involved in an organization aiming to make a real-world impact. When I started teaching civics here [at Northwestern], we used a community consulting model, where students worked with a community partner to create a deliverable, like a plan or an event.

However, the issue with these kinds of projects is that they’re “hand off” projects, where students create something to hand off to the organization. While useful, this model doesn’t necessarily teach students the skills to build an organization that can make policy change because they aren’t deeply embedded in the organization’s core work. As a result, students may not learn the skills needed to create change as engaged citizens. Also, the community consulting projects may not help the community organization much.

We began rethinking what core skills are needed for social change. Social change can involve community development, where you bring people together to create an impact, often through nonprofits, or social action, where you create pressure on decision-makers, like elected officials, to change policy. Both require organizing skills. To teach students to work in organizations, we first tried involving students in the participatory budgeting process in Evanston, which provides an infrastructure where students and community members can practice democratic processes, community development, and many aspects of social action. It’s a great way to create a democratic structure that teaches people how to be active citizens.

However, city-wide participatory budgeting is an intense first step for a college student. It involves complex project planning, attending weekend and evening meetings, talking to strangers, and engaging in debates. These are all valuable skills, but it presents a quite ambitious learning challenge for a 101 level course, especially since students aren’t typically getting this kind of educational experience in high school. To adjust the level of challenge, we created a campus-based participatory budgeting process, where students run a smaller budgeting process. This allows them to practice all the skills and have an impact, but it’s more manageable and doesn’t feel as overwhelming.

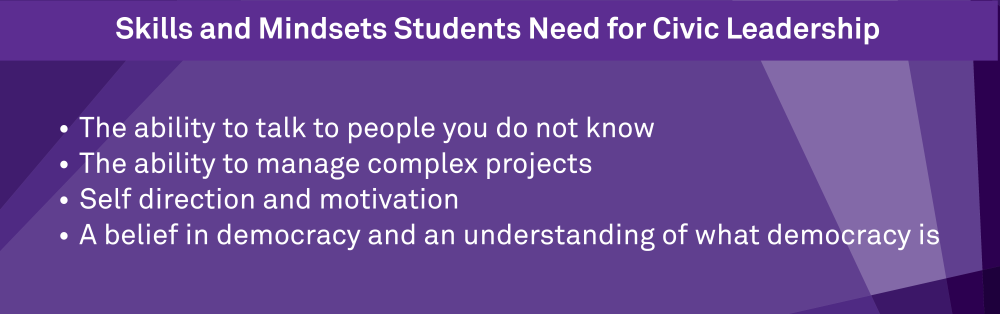

Corwith: What are some of the skills and mindsets students need to hone early?

Easterday: One critical skill is being able to talk to strangers. That is huge. That is so hard for many people, and my experience, even with students here at Northwestern, is that they don't have a lot of practice doing that. It can be a big challenge.

Another set of skills is managing complex projects and self-direction; so, the kinds of skills and strategies you would teach in a project-based learning class. Students need many more opportunities for doing that work. They also need access to a diverse network of peers, community members, and leaders.

This may sound like a weird one, but I think it's really important: a belief in democracy and an understanding that democracy isn’t just voting. There's a lot more to it than that. And along with that understanding is the commitment to citizenship. Honing the mindset that you are part of the community, and you are responsible for it and that with the right democratic structures, we can govern ourselves.

Corwith: You have talked about the courses you teach. You also conduct research. Your research interests are at the intersection of technology and civic education. On your website it is described as “producing scientifically supported educational technology to create informed and engaged citizens who can solve the serious policy problems facing our society.” Tell me, with an audience of parents and teachers in mind, what this work looks like in practice.

Easterday: As a graduate student, I worked with a technology called intelligent tutoring systems. These are AI programs that know how to solve problems such as an algebra equations, for example. A student will solve a problem on a computer while the AI solves it simultaneously. The AI monitors the student’s work and gives feedback if they make a mistake, like a coach offering guidance. Studies have shown these systems can improve performance significantly.

However, this approach only works for really well-defined domains, like solving math and physics problems. So, my research explored whether we could teach skills like argumentation and using evidence and causal reasoning—skills critical to civic engagement—in the domain of policy. We did it by developing an AI system focused on causal reasoning and embedded it in a game-like environment. This approach allowed us to make reasoning skills “tutorable” by the AI while assuring the process was engaging for students.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · Feeling Empowered Despite Uncertainty

Fast forward a few years, and my work transitioned to tools for helping teachers design and implement project-based learning, since it is a time-intensive approach to implement well. This system, called Loft, included guides, team management tools, and a feedback and critique system for student work, which made giving and receiving feedback much more effective.

Most recently, we have been applying these principles to civics education, which presents unique challenges but has a lot of potential opportunities. While we initially treated civics as a design and project-based learning activity, my team and I realized that making a real community impact requires students to work within organizations and develop organizational skills. This shifted our focus, and we secured a grant from the National Science Foundation to develop tools for deliberation. We explored how to facilitate group discussions, where participants come together to discuss a topic and propose policy ideas.

Now, we’re working on a system called Deliberation Works, which supports both deliberative discussion and the organizational aspects of community engagement. It helps track engagement, outreach, and engagement activities, combining elements of mailing lists, project management, goal setting, and discussion tools. It’s a very different set of features from what we developed for the original project-based learning courses, but it still utilizes technology to support, guide and facilitate learning.

Developing and making available this type of technology can help educators teach students the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to analyze policy, communicate issues, and organize effectively.

The Transformative Power of Service-Learning for Young People

Service-learning is an educational approach that combines meaningful community service with academic objectives, inspiring young people to grow as engaged and compassionate citizens. It is the bedrock of CTD’s Civic Education Project and related programs. Unlike traditional learning, service-learning offers hands-on experiences that bring classroom lessons to life. While students engage with texts and other resource materials, they spend a significant portion of their time learning in communities and engaging with individuals living and working in those spaces. Whether visiting innovative healthcare clinics to understand access issues, engaging with nonprofit and government leaders on immigration policy, or working in tandem with community organizations to provide meals, students gain eye-opening perspectives on real-world challenges. These immersive opportunities sharpen students’ critical thinking, perspective taking, problem-solving, and leadership skills, fostering a sense of responsibility and a deeper understanding of how they can contribute to social good.

By connecting service activities to academic frameworks, service-learning helps students make interdisciplinary connections and integrate their experiences with classroom learning. This deliberate approach attends to students’ intellectual development and affective skill development while exploring genuine community needs and resources.

Learn more about CTD’s approach to Civic Education and Service-Learning and explore upcoming courses.

Thinking about Civic Engagement from Elementary School through College

Northwestern University’s Center for Civic Engagement facilitates engaged student learning and promotes a lifelong commitment to social responsibility and active citizenship. But this learning should not, and is not, reserved only for adults.

Young people can have a significant role in and impact on their communities, and they benefit from early development of critical thinking, social, and leadership skills through experiences that emphasize the importance of socially responsible leadership and the need for talented young people to use their abilities to address pressing global challenges. The connection and collaboration between CTD and the Center for Civic Engagement showcases a shared commitment to cultivating a PreK-16 pipeline that equips young leaders to drive meaningful change in their communities.

Read more about CTD's long-standing relationship with Civic Education.