Winter 2023

Talent Newsletter

Talent Newsletter

In this issue of Talent: Director's Message: Understanding Eminence in the Talent Development Framework | The Long Road toward Eminence: A Conversation | A Profile of Eminence: CTD Alum Anthony Sparks—Artist, Scholar, Cultural Interventionist | CTD Sidebar: From CTD to Comic-Con

How do individuals come to make groundbreaking contributions to their fields?

Last year, a special double issue of Gifted and Talented International considered what factors lead to eminence—individuals becoming the most innovative and influential in their fields. Nine articles addressed eminence, which is the term used to describe transformational achievements and creativity in a domain or field, from a variety of perspectives and applications—including academics, geopolitics, athletics, and the arts—and across time.

Frank C. Worrell, Rena F. Subotnick, and I co-authored an article centered on the talent development trajectory from potential and achievement in youth to expertise and, for some, eminence in adulthood. This long-term process stands in contrast to the notion that gifted education is a school-based construct that has relatively short-term aims, for example, admission into one’s college of choice.

You can't predict who will become a high achiever or achieve eminence. It's a long journey filled with many ups and downs and chance occurrences. In talent development, particularly as applied in the K-12 setting, we do not suggest that educators should be focused on eminence but rather helping young people find their interests and strengths, identify and take opportunities, and maximize their potential utilizing the best practices in the field so that they are prepared for the next stage of talent development. However, if educators know the components of the paths that lead to STEM careers, an authentic research experience for example, they can provide them and better insure that students get on their desired paths . Every child deserves the opportunity to learn and grow to their fullest potential. With the right approaches, we can support these journeys toward personal fulfillment, real progress on major social issues, and contributions to areas of art and athletics that fuel the human soul.

You can't predict who will become a high achiever or achieve eminence. It's a long journey filled with many ups and downs and chance occurrences. In talent development, particularly as applied in the K-12 setting, we do not suggest that educators should be focused on eminence but rather helping young people find their interests and strengths, identify and take opportunities, and maximize their potential utilizing the best practices in the field so that they are prepared for the next stage of talent development. However, if educators know the components of the paths that lead to STEM careers, an authentic research experience for example, they can provide them and better insure that students get on their desired paths . Every child deserves the opportunity to learn and grow to their fullest potential. With the right approaches, we can support these journeys toward personal fulfillment, real progress on major social issues, and contributions to areas of art and athletics that fuel the human soul.

I’m excited to share in this issue of Talent the surprising and intriguing findings we’re uncovering through our research and, most importantly, how we as parents and educators can apply these findings and continually strive to improve the opportunities, access, and overall educational experience for our students.

![]()

Paula Olszewski-Kubilius

In 2021, Frank Worrell, Rena Subotnick, and Paula Olszewski-Kubilius published “Giftedness and Eminence: Clarifying the Relationship” in Gifted and Talented International. They explored how historical and cultural context, opportunity, environment, intelligence, mentorship, concerted effort over time, and luck all play a role in the progression from potential to eminence, a term used to describe individuals who have a transformational impact on their field or change the world for the better.

The article also presented their talent development mega model (TDMM), which is aimed at positioning outstanding achievement as the ultimate goal of gifted education. Rooting definitions of giftedness in achievement, the model refutes previous frameworks that postulated that “once a child is identified as gifted, they are gifted for life.” regardless of what they do. Principles at the core of the TDMM model include:

Returning to the topic a year later in an interview for CTD, Drs. Worrell, Subotnick, and Olszewski-Kubilius unpack the perceptions, controversies, and opportunities of eminence as a goal.

"Our view is that talent development is a lifelong process, and if a student has the abilities and aspiration to be eminent, we as educators need to be prepared to support them along their pathway."

- Dr. Rena F. Subotnick

Worrell: Some people dislike that eminence is the top level in our model because they believe in the idea of being gifted for life, or they view eminence as too exclusive. We argue that while in childhood, giftedness is rooted in potential and achievement, in fully developed talents, giftedness moves beyond potential to expertise and eminence.

Subotnick: Another concern was what an elementary school teacher has to do with eminence. Our view is that talent development is a lifelong process, and if a student has the abilities and aspiration to be eminent, we as educators need to be prepared to support them along their pathway.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · Strategies For Nurturing Students Through Transformational Creativity

Olszewski-Kubilius: Some readers believed we were suggesting the field should only focus on people who could reach eminence. Rather, we suggest there are things we could provide children in school that might increase their odds of becoming high achievers and moving into the levels of expertise and eminence.

Subotnick: Teachers don’t need more burdens. For professional development, however, we can encourage teachers to join domain associations or organizations. For elementary generalists, we can encourage awareness, for example, of enrichment and acceleration opportunities in the community—and scholarships if necessary—as well as the optimal placement in middle or secondary school for students with talent in a domain so that they can share this information with parents. This information should be widely disseminated, but strongly promoted for the students with identified domain talents. The domain-specific approach, enriching students in their strength area, makes the work of teachers more concrete than serving the gifted in relation to high IQ.

Worrell: There are some teachers who already do this, but often with a selective group. For example, they may consider one or two top students and recommend a book or after school activity to them. Because this pathway is not necessarily linear, teachers need to look more deeply into their classes, beyond top scorers, to students who are passionate about an area—using joy and excitement as a way of identifying kids for whom to make special recommendations.

Olszewski-Kubilius: Schools should be prepared with domain trajectories for talented students (for example, competitions, summer programs, and research opportunities for aspiring writers, artists, scientists, and historians) while allowing for late bloomers and those who lose interest in one domain for another. While each student's path is highly individual and somewhat idiosyncratic, some common themes emerge, and teachers can help direct kids toward these pivotal experiences. Teachers of young students could add curriculum beyond the basics: opportunities for enrichment or for independent projects and investigations. Schools can add enrichment opportunities to the school setting via after-school programs and clubs, open to all students based on interest. Teachers can also bring in people from the community to show students what various professions or domains look like. As kids get older, subject area teachers can recommend outside-of-school opportunities to students and parents. Students should be placed in appropriately challenging courses that they are ready for and accelerative options should be used as appropriate. Schools should work collaboratively to connect kids to educational experiences beyond their own building or district.

In our recent work, the three of us interviewed STEM professionals who reached really high levels in their careers. Often interviewees mentioned similar kinds of experiences that were really important to them, like competitions in math, or opportunities in summer programs where they received a lot of support and found other kids who were really interested in those topics.

Subotnick: Peer support and friendships with individuals with the same affinities and interests are optimal for development. It can be difficult for any individual to not have support for their interests and goals. Often, it is only in specialized programs and summer opportunities that some students find this peer support, making all the difference to their happiness and motivation.

Worrell: I don't agree with the premise that a student who has been classified as gifted is necessarily going to thrive on their own. We focus on talent development because we know that moving to higher levels takes input on the part of the student, appropriate teaching, and opportunities provided by teachers. There are students who may be high functioning in elementary schools, but if they don’t receive the right educational accommodations and investment, their pathways may go differently.

Olszewski-Kubilius: Without the proper opportunities and encouragement to pursue them, many individuals fail to develop their potential—to society’s detriment, but also, unfortunately, with negative effects for them in terms of loss of self-esteem, creativity, and even income.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · The Importance of Schools Helping Gifted Students

Worrell: There is also an ethical aspect we need to think about as a society. Special education was developed so that every child could get a free appropriate public education. Courts have applied the standard of free, appropriate public education to children with disabilities. It should apply across the board—we want every child to receive a free, appropriate public education. For students who are gifted and talented, that means getting opportunities like acceleration, special programming, and so forth. Parents who make over $200,000 can send their children to specialized programs, and many of them may succeed. But think about all of the kids who have potential but don't come from high-income households. School is really important for those students in particular.

Subotnick: As a secondary consequence, lifting those below grade level and doing nothing for everybody else delivers a message that high expectations and high achievement are not valued.

Worrell: The literature on this is tremendously mixed. In creative fields, there are individuals who have come out of challenging circumstances and achieved eminence. But I don't think that is true across the board. The most recent example is the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth (SMPY) data. When you look at those students now in their fifties and sixties, they seem to be flourishing. Many are reporting not just academic or occupational success but life success, such as being happy or married.

"Teachers need to look more deeply into their classes, beyond top scorers, to students who are passionate about an area—using joy and excitement as a way of identifying kids for whom to make special recommendations."

- Dr. Frank Worrell

Of course, there are going to be kids who achieve eminence who have vulnerabilities. Every population has them. I don't think there's evidence to suggest that eminent individuals have vulnerabilities at a greater level, or if they do, that it's the result of being eminent. It may be the result of having to deal with the pressure or fame associated with success, for example, the paparazzi.

Olszewski-Kubilius: The literature supports that there are some greater vulnerabilities among people who are creative, particularly creative writers. But there's no research to support that these individuals are inherently wired differently. Just like any other group, the circumstances of their lives are what interact to make them more or less vulnerable or psychologically healthy.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · Preparedness And Psychosocial Skills for Gifted Students

Subotnick: We're learning every day from headlines, from our own experiences, that people need psychological support for being in these rarefied environments. If you're in a very unusual, high-pressure environment, you may need coaching, preparation, or performance support, which the three of us have very strongly promoted as part of talent development. When you already know that if you are going to be very creative, you're going to upset a lot of people, it's not quite so traumatizing as when you get pushback. When you expect it and you’re prepared, you may even be able to co-opt it.

Subotnick: The optimal age in each domain for broad versus narrow focus is a ripe question for further research. It differs across domains, and we don't have research that really informs policy.

For example, a student is exposed to many areas and finds out they like STEM. After pursuing this they reach a level at which they can't answer their own questions without reading about or being exposed to another STEM domain, or an art domain, or politics. This shifting of focus goes back and forth in every domain. If children can be nurtured to try their best, to enjoy the fruits of practice or study, they should be healthy. If they confuse these messages with love and pride coming with success, the outcome is iffy. They'll get success with regret, or they'll give up.

Worrell: It’s a question of development. In some fields, if you push specialization too early before the body is matured, for example in some sports, you are going to do damage. Early investment in a domain may be playing rather than deep study. We are also well aware of this idea of pulling things from different areas—that spatial thinking ability, for example, contributes to thinking about the DNA strands. Knowledge that may not appear to be related to what you're doing may actually be what stimulates a creative response and advancement. That speaks to the importance of having breadth alongside depth.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · The Relationship Between Eminence and Specialization

Olszewski-Kubilius: Research shows that many people who become eminent, or appear to be highly specialized, have really well-developed abilities in another area. Most notably, a large number of eminent scientists were deeply engaged in an art form and had been since childhood. These individuals look “one-sided” only because we really only know their accomplishments in their specialty area.

Well-roundedness is important early in the sense of exposure to a variety of fields and nurturing of early interests, until a passion develops. The idea of “well-roundedness” is highly individual and is often confused with good social and psychological skills and functioning. Nurturing those skills is essential for all individuals, regardless of when they specialize. Specialization does not preclude good mental health and robust social lives. Promoting good psychosocial skills doesn’t mean doing a bunch of different activities, but rather having sustained interactions with other kids, and in several environments.

When kids go to summer programs where they participate in competitions, those activities build social and psychosocial skills. In our study of the super users of CTD programs, we looked at students who used our programs over a period of years and were involved in many courses. It wasn’t unusual for students to come to an area that really intrigues them, and to stay with it, in middle school. That's not too early to specialize.

Worrell: At our summer program, students specializing in specific areas may take a variety of courses addressing different aspects of the domain over several summers, for example, creative and technical writing. Within the specialization, there's also breadth. And we were surprised at the number of extracurricular activities that many of our students participated in. We've had students who've asked for accommodations to participate in student government for a week in Sacramento, to dance in Miss Saigon on Broadway, or to practice skiing as part of the junior Olympic team.

Subotnick: We need to acknowledge that fields change and transform. If talent development is guided by mentors who are active in a domain, they would most likely monitor important changes in terms of talent development preparation and experiences, keeping young people involved and informed. It would be appealing to many kids to participate in a domain that is dynamic and responsive to their generation.

Olszewski-Kubilius: We also need to separate accomplishments at the individual level—ones that are personal but nonetheless important—from ones that impact society. That being said, we can help individuals who train others in their domain to broaden their picture of what is success. For example, a university professor who trains graduate students can be open to accomplishments that follow a traditional path (e.g. publications, presentations, grants) to other types (e.g. being a public figure, recognized as a public spokesperson in a field, writing for a lay audience on topics in the field). This will involve diversifying the faculty in high-level training areas and valuing people who go in a different direction, for example, a student who pursues applied versus basic research.

Universities are trying to grapple with this because there are more endpoints for students after they graduate. Whereas graduate students were previously trained, often by professors entrenched in academics, to go into academics, many students today are following different trajectories, such as working at startups and companies doing innovative work. Professors are trying to adjust and become better versed in preparing students for opportunities they themselves don’t aspire to.

Worrell: Fields are evolving and diversifying. A number of students who are graduating from psychology programs are being hired by companies like Google and Facebook. These were not opportunities that existed 20 years ago. There’s a greater wealth of opportunities now, and I think that's going to continue. People with PhDs in chemistry and biochemistry creating new vaccines for biotech and pharmaceutical companies have not gone into an academic environment but are making extraordinary contributions to society. But they're not necessarily visible or winning Nobel prizes.

Subotnick: Some fantastic scientists got the Nobel prize this year, but not the ones who invented MRNAs, potentially saving millions of lives. Maybe science is less responsive to trends than other domains. On the other hand, the Nobel Peace Prize went to activists associated with the Ukraine war. Galleries, movies, plays, and other artistic endeavors are engaging the talents of African American artists in response to recent events and a new awareness of systemic racism.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · When Is The Right Time For Specialization?

Olszewski-Kubilius: Timing does impact how fields evolve. I introduced the idea of moving the field of gifted education to talent development over 10 years ago. It was not received well even though the kernels of that idea were present in the writing of other scholars 20 years ago. The timing was not right, and the field was not ready. Now, however, everyone is talking about talent development. Programs are changing their names from gifted to talent development. The current context, with the focus on justice and equity, is much more conducive to this shift.

Subotnick: In recent years, more and more important work is conducted in teams rather than by individuals. There can be eminent teams as easily as eminent individuals.

Olszewski-Kubilius: Societies and cultures place values on fields and revere some domains (e.g., spiritual, healing, artistic, leadership, intellectual) more than others. There are also generational differences. An upwardly mobile family may press children to enter economically lucrative fields whereas a family with some generational wealth may be very supportive of a child entering a creative field with much less financial stability.

Subotnick: Countries that claim their greatest natural resource are their children (e.g. Singapore or India) are more logically likely to encourage outstanding performance and provide support. We are starting to see that in India. The United States stands out in areas where individual initiative or physical prowess is key. In areas where intellectual prowess is most essential, we benefit from those who come to the US after being schooled in other countries.

Olszewski-Kubilius: Other countries are much less bothered about providing educational opportunities to individuals they perceive as already advantaged (i.e. gifted children) than the US. These are countries that tend to feel nurturing talent is in their national interest. On the other hand, the US is probably ahead of most countries in terms of the gifted field's commitment to serving children from low-income backgrounds and minoritized groups, especially with its recent and hopefully enduring greater focus on talent development.

Frank C. Worrell is the 2022 President of the American Psychological Association (APA) and a professor and faculty director within the School of Education at the University of California, Berkeley. Rena F. Subotnick is director of the Center for Psychology in the Schools and Education at the APA. Paula Olszewski-Kubilius is director of the Center for Talent Development at Northwestern University and professor in the School of Education and Social Policy.

Listen to the full interview on Soundcloud

Read more from Frank C. Worrell, Rena F. Subotnick, and Paula Olszewski-Kubilius

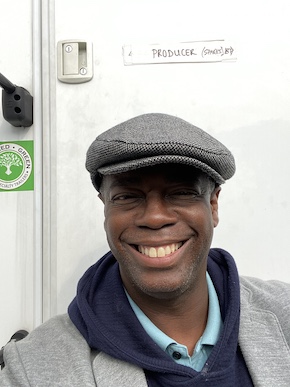

Center for Talent Development (CTD) alum Anthony Sparks, a drama writer, producer, and showrunner, has reached top creative and managerial positions in the entertainment industry, particularly television. Through award-winning shows including Queen Sugar and The Blacklist, and new projects like Mike and Bel-Air, Sparks is diversifying the lens through which we see the world. “Television, streaming, and cinematic storytelling are the language of twenty-first-century popular culture,” notes Sparks. “I consider myself a participant in expanding that language as a Black writer, producer, showrunner who comes from the inner city, but who has also been blessed to have expansive experiences in life. I'm trying to disrupt the notion of what a Black man is, what a Black woman is, what a brown, Latino or Latina, Latinx person is—what we all are as human beings. That is what I consider to be part of my life's creative and intellectual work.”

Opening the industry by hiring diverse teams of writers, directors, and producers is another important legacy of his work, particularly on Queen Sugar. “I'm very proud to have run the show in such a way that it could be a strong force in advocacy for advancement in terms of diversity, equity, and inclusion,” says Sparks.

Like many individuals who achieve at exceptionally high levels and transform their fields, Sparks benefited from mentorship and advocacy along his journey. As an elementary school student on the South Side of Chicago, Sparks had mistakenly been relegated to a “slow track” in terms of how students were placed for instruction at that time. “And I remember there were three Black teachers at my elementary school who surrounded me and said ‘no, you got it wrong with this kid.’ They advocated for me,” says Sparks. “They were the first ones to advocate for me outside of my own mother advocating for me and believing in me.” Sparks excelled in school and eventually matriculated at Whitney Young Magnet High School, a selective enrollment school of the Chicago Public Schools.

Like many individuals who achieve at exceptionally high levels and transform their fields, Sparks benefited from mentorship and advocacy along his journey. As an elementary school student on the South Side of Chicago, Sparks had mistakenly been relegated to a “slow track” in terms of how students were placed for instruction at that time. “And I remember there were three Black teachers at my elementary school who surrounded me and said ‘no, you got it wrong with this kid.’ They advocated for me,” says Sparks. “They were the first ones to advocate for me outside of my own mother advocating for me and believing in me.” Sparks excelled in school and eventually matriculated at Whitney Young Magnet High School, a selective enrollment school of the Chicago Public Schools.

When he was about twelve years old, Sparks was introduced to CTD by educators at his school and he took a summer course in biology. “Even though it was just a three-week program, over 35 years ago, it remains one of the most seminal summers of my life,” notes Sparks. “That [experience] expanded my world even more, meeting kids just like me intellectually and creatively from all over the country.” During the last two years of high school, Sparks also had the opportunity to participate in the NU Horizons mentorship program run by Dr. Joy Scott, which was a monthly college prep and workshop program.

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · The Importance Of Pivoting

Being in these specialized, talent development programs and working with exceptional mentors encouraged Sparks to think differently about his goals, his abilities, and where he still had room for growth. At CTD, for example, Sparks says, “I discovered that as smart as I thought I was, I was not the smartest kid around—one of the best things that ever happened to me.” The programs, his hard work, and the support of mentors also helped him chart a pathway to future college and career choices. At Whitney Young, he fell in love with theater. He ultimately was recruited by several highly regarded theater programs and received a scholarship to study theater at the University of Southern California (USC). Following graduation, Sparks launched a career acting on and off-Broadway in New York, including traveling internationally as a cast member of Broadway hit Stomp.

Motivation, persistence, and self-efficacy are also important psychosocial skills Sparks points to in reaching the highest levels of talent development. Like many actors, Sparks auditioned and picked up a variety of jobs: in voiceover, commercials, and auditioning for TV and film. “As a young Black male actor in the mid and late '90s the landscape for opportunity was not what it is now. It's still problematic now, but it was even more problematic then.…Casting directors would tell me they didn't think that I was ‘urban’ enough or ‘Black’ enough. It disturbed me then. It disturbs me now because I am from the inner city, but I wasn't what the industry interpreted as from being from the inner city,” says Sparks. Over time he found himself feeling like his acting opportunities were being limited, and this is where the nurturing he had received, through CTD and other programs he participated in, came into play. He had the confidence to pivot, to transition from acting to writing, where he could have an influence on the stories being told instead having to fit into somebody else’s idea or image. Sparks believes it was important for him to acknowledge that he had talents other than the ones he had been known for, which, at the time, was being a skilled performer. While Sparks says he was deeply frustrated and angry about barriers he experienced in acting, he also had a determination, the vision, and the ability, to try and change the system.

“If you are deeply interested in something, I would advise you to pursue that without necessarily knowing exactly where it ends up. It doesn't always work out the way that you want it to. That doesn't mean you can't work out in a way that's beneficial to you and your life and to the world.”

-Anthony Sparks

Sparks began concentrating on writing and putting on his own plays with ambitions to change the images and stories perpetuated in television, film, and theater. “I could do that cultural and interventionist work if I was coming up with the ideas in the first place,” notes Sparks. Writing plays opened doors to write for television and film, leading him back to California and eventually academia. Sparks pursued a PhD in American Studies in Ethnicity from USC to inform his interventionist work and to bridge the gap between practitioners and academics. “I was looking for a space to think through very seriously how to use the tools of pop culture to have robust conversations while also entertaining people. I didn't want to just go off of my own experiences as valid as they are. I wanted to be steeped in history and understand that what I was contributing to was part of a long running debate and conversation about people's humanity across the spectrum…. I am deeply interested in creating stories that entertain but also edify, question and probe, and provoke if necessary.”

Sparks is passionate about working simultaneously in television and academia. He is as an assistant professor of cinema and television arts at California State University. “Education is super important to me because so much of what my life looks like is because people acknowledged that I had ability,” says Sparks. “I want to pass on my experiences and knowledge so that me being one of only a few Black male drama showrunners in television ends with me.”

Center for Talent Development at Northwestern · Giving Up The Need For Perfection

Sparks argues that skills in persistence and releasing the need to be perfect contribute to long-term success. “To get to those 10 yeses that now go on to my bio, there were a hundred times where I hung up the phone from my agent or manager and cried because it was a really painful no.” It can be challenging for students accustomed to being recognized for their talents to release the need to be perfect or not feel like a failure if someone did something better. “We can all work towards excellence, but being a perfectionist is chasing the impossible, and it can lead to toxic behavior,” says Sparks. “Being gifted and developing your gifts doesn't exempt you from hard work, or from making mistakes on the job or in life.”

Read more about Anthony Sparks

1980s alum Douglas Wolk teaches and writes about comics, including exhaustive Marvel history

By Ed Finkel

Douglas Wolk was already a comics aficionado by the time he spent a few summers at CTD in the mid-1980s, and he didn’t take any comics-related courses at Northwestern—he recalls studying math and computer science—but he believes the program nonetheless has had considerable influence on his career as a writer and, now, professor.

A magazine, newspaper and website writer who covered the music scene for many years before shifting over to comics, Wolk recently published his fourth book, “All of the Marvels,” a comprehensive history of the six decades of interwoven storylines and an examination of how the comics series influenced—and was influenced by—American culture and politics. His career to date also has featured bylines in publications like Rolling Stone, Entertainment Weekly and Pitchfork, along with lecturing and moderating panels at Comic-Con and similar conferences.

Wolk remembers getting hooked on comics in earnest at age 9, when he picked up an issue of Green Lantern/Green Arrow while visiting his grandparents in upstate New York, and read it repeatedly. He animatedly recalls his frame of mind upon returning home: “'I have to find out what happens in the next issue. Oh, and this character is also in this other comic. I should pick that up, too. And oh, there’s a store that sells nothing but comics that’s a couple miles from my house. And they get new comics every Friday? I know what I’m doing every Friday now!'”

Wolk remembers getting hooked on comics in earnest at age 9, when he picked up an issue of Green Lantern/Green Arrow while visiting his grandparents in upstate New York, and read it repeatedly. He animatedly recalls his frame of mind upon returning home: “'I have to find out what happens in the next issue. Oh, and this character is also in this other comic. I should pick that up, too. And oh, there’s a store that sells nothing but comics that’s a couple miles from my house. And they get new comics every Friday? I know what I’m doing every Friday now!'”

As time went on, Wolk had become so well-known at that store that the owners hired him part-time as a teenager. And both times he attended CTD, “My comics store held onto my new releases for three weeks, and I read them when I got back.”

Wolk began his career as a pop culture critic in the early 1990s, mostly covering music, when the editor-in-chief of CMJ New Music Monthly, where Wolk served as managing editor, suggested that he start reviewing other types of media, including comics. His work there led to opportunities writing about comics for an Australian magazine called World Art, and then publications like the Village Voice and the New York Times.

Wolk continued writing about a mix of music and comics until the mid-2010s, when he thought to himself, “You know what? A lot of people write about music. Not a lot of people are writing for a mainstream audience about comics. I want to concentrate more on that.”

Along the way, it’s led Wolk into academia as a National Arts Journalism Fellow at Columbia University, a Fellow in the USC Annenberg/Getty Arts Journalism Program, and most recently as a professor at Portland State University, where he generally teaches one class per year.

Wolk also has penned a few books about comics, after writing his first tome, “33 1/3: Live at the Apollo,” about a performance that soul singer James Brown gave in Harlem during the Cuban Missile Crisis. A couple years later, he published “Reading Comics,” which won a Will Eisner Award for Best Comics-Related Book. Next up was “Judge Dredd: Mega-City Two,” which provided him the opportunity to actually write a comic mini-series, “which was enormously fun.”

Wolk’s most recent book project, “All of the Marvels,” was originally inspired by his son, who suggested that they read all 27,000-plus Marvel superhero comics—totaling more than 500,000 pages. While his son didn’t quite make it to the end, they do read a comic together every night as a family. And the concept got Wolk to thinking.

“I had been casting about for some kind of big, juicy project I could do. What if I actually read all of them?” he says. “What would the 60-year-long story look like as a story? What would it say about not just itself and its content, but about the world around it, the world that produced it, the world it was born into? And that became the idea for the book.”

Initially, Wolk thought it might take a year to complete the reading and another 8 to 10 months to write the book. Six-and-a-half years later, it was published—and he found the process even more fascinating than he expected. “I realized pretty early on that the Marvel comic story is this amazing, distorted and blown-up, more colorful history of American culture in the last 60 years,” he says. “They are always about what is on their creators’ minds. And sometimes that’s in obvious, referential ways, and sometimes it is in just kind of dramatic ways.”

"Realizing that there were other people who were like me, and also saw the world very differently for me, and that we could learn all kinds of stuff from each other—that was invaluable. That saved me as a teenager and opened up this world of learning to me."

-Douglas Wolk

When Wolk looks back nearly 40 years after matriculating at CTD he can see clear through-lines that made him the person and writer he is today.

“What was valuable about CTD for me was the experience of being around peers, around kids who were my age, who were really, really interested in thinking, and learning, and seeing how each other’s minds worked,” he says. “And there are social connections that I made in those programs … who are people I’m still friends with, now. Realizing that there were other people who were like me, and also saw the world very differently for me, and that we could learn all kinds of stuff from each other—that was invaluable. That saved me as a teenager and opened up this world of learning to me.”